Issue twenty-nine of Brian Moore’s Head, the second edition of the 1992-3 season, went on sale for the first time before the game against Walsall at Priestfield on Saturday 25 September 1992. It was the ninth league fixture of the campaign and the Gills had only won one out of the previous eight.

The Barnet home match on the last Saturday of August had attracted a crowd of 3,874, yet only 2,503 came through the turnstiles, three days later, when Wrexham visited for what would turn out to be Gillingham’s only win in their first thirteen division three fixtures.

The editorial in BMH29 commented on the large difference between the two gates and then moved on to complain about the way that the club was treating their supporters, ‘The prices this season at Priestfield seem to be about average for the third division this season.

However, £6 is still a lot of money, and the prices probably explain the fluctuation in our attendances when we have played two home games in four days. People are having to pick and choose their games and it was fairly obvious that a Saturday game with Barnet would draw in a lot more than Wrexham on a Tuesday. Our prices could have been higher.

There was one member of the board who wanted to charge £7. Such a price would have been a rip-off, as was the eight-page black and white programme for the friendlies, selling at £1. It had a price of 50p on it when it went to the printers.

Justification for the price of £1 seemed to be that the club received no complaints about it. I know for a fact that there were quite a few of the Ipswich fans who came down for the friendly who were not happy about it and, although there were no complaints, a lot of supporters knew that Gillingham Football Club (who are so keen to have us turning up, week in, week out) had ripped them off.

Admission to home reserve matches had been free to season ticket holders, a nice gesture. At the first reserve game this season, it was £1 all pay. Now I’m not bothered at paying for the games when they used to be free, what annoys me is that the club didn’t have the decency to inform us of the change in procedure. It would have been nice. We’ve got a programme, anything you want to tell us, why not put it in there?’

After it had taken three and a half years to finally sell out of the third edition of the fanzine, BMH29 mentioned that ‘it looks like we could have a fiasco of issue three proportions on our hands with our last effort. It’s all my fault, readers, as I foolishly elected to have an extra one hundred copies printed in a fit of pre-season optimism.

Basically, we didn’t actually sell any more than we usually do, so if anyone wants to make a bulk purchase of issue twenty-eight, we’re open to offers.’ The letters page in issue twenty-nine contained one of the most blatant space-fillers that the fanzine ever managed, ‘Dear BMH, Have you ever been working on a fanzine, only to find out that you have been left with an annoying gap on the letters page? This happened to me the other day, and I thought the readers of BMH would like to read all about it. Well, it’s better than looking at a blank page, isn’t it?’ The letter was from A.N. Editor from Rochester.

By the time BMH29 was out, Sky had launched their live football coverage and the article ‘Pie in the sky’ was about the first game shown on ‘Super Sunday’, Nottingham Forest v Liverpool. The programme started at 2pm, but ‘the game didn’t actually kick-off until 4pm, so what we had to put up with was a tiresome two-hour build-up before the match.

Former TV-AM man Richard Keys, and Andy Gray, plus Chris Waddle, spent most of the time waffling on and on about nothing in particular, although I have to say at this point that Andy Gray is one of the best commentators around, always pointing out the little niggles between players and also saying what he thinks where other commentators would say nothing.’ Four o’clock finally came round and the fixture got underway, ‘As the match progressed, I happened to notice something in the corner of my screen, which stayed there for the rest of the game.

I tried rubbing it off, thinking it to be a big smudge on the TV, but apparently it was telling me the score and the time elapsed in the match. You could have fooled me, I went and got my binoculars and checked the screen and, blow me, it really was telling me the score and time elapsed.

Well, what a great new innovation – not!’ Once the game had finished, there was a phone-in where ‘you, the fans, can have your say’. The writer was not impressed with the quality of calls, ‘This was yet more riveting TV, as we had calls about how David James had a tremendous game on his début, for crying out loud! I know, I’ve just watched the game.’ Finally, the programme came to an end, ‘Really, I don’t know how they manage to fit ninety minutes of football into this five-hour spectacular of inane chat and drivel.’ It didn’t stop him tuning in again the following evening for ‘Monday night football’, ‘Thankfully, this was just a three hour feast of chat with a football match thrown in there somewhere.’

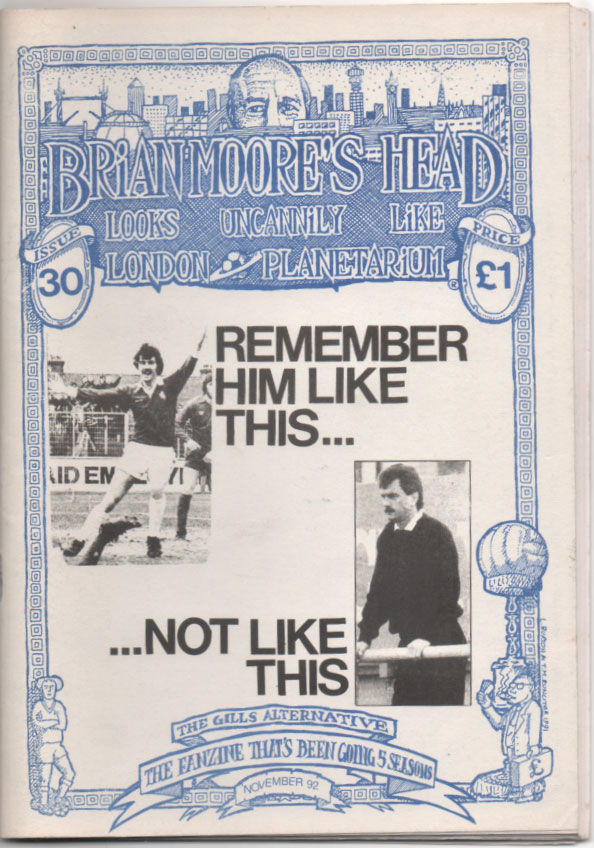

On the afternoon of Thursday 8 October, the day after the 3-0 loss against Southampton at The Dell in the Coca Cola (League) Cup, Gillingham manager Damien Richardson was sacked. BMH 29 had only been out for less than a fortnight and, with the next edition not due until at least mid-November, the publication date being dictated by whether we got a home draw in the first round of the FA Cup, there was plenty of time for contributors to comment on the departure of the Irishman.

The editorial began, ‘So, the inevitable finally happened, after yet another defeat, and with the team just one place off the very bottom of the Football League, Damien Richardson paid the price for his failure to build a successful team. And, let’s make no mistake about it, it was going to come sooner than later, and it is better for all concerned that it came sooner.

In the aftermath of the sacking, there was an awful lot of nonsense talked in the local media, all this did was to demonstrate how out of touch with reality some individuals are. Sure, there are those who believe the sacking was a mistake but, to them, I would ask this question, how low would you have allowed us to sink before getting rid of Damien, because there were absolutely no signs of a recovery on the horizon.’ The general consensus of opinion amongst the contributors was that Damien was a nice bloke but that he simply couldn’t be allowed to continue as manager, ‘I was among the 99% who liked the man, recognised his loyalty towards and ambitions for the club and longed for him to succeed.

But Damien’s skills had been stretched to the limit at Gillingham. The side were no longer improving in the way they did in his first couple of campaigns, when he undoubtedly halted the slide. The team we have been fielding has been entirely built by Damien and it is no more than a mediocre basement outfit. He failed to recognise its major shortcomings, such as the failing sweeper system, frail centre of defence and lack of width.’ Also departing with Richardson was assistant manager Ron Hillyard, whose sacking ended his eighteen year spell with the club.

Damien’s replacement had already joined the club by the time BMH30 appeared, ‘It is obviously far too early to judge whether the appointment of Glenn Roeder is the correct one, but I have to confess that my initial reaction is favourable. I was delighted when I learnt that one of his first actions was to order the players in for extra training. This is just what was needed, too many of the squad had been performing well below what they are capable of.’

One of the first away games of the 1992-3 season had been the visit to Rochdale for a Tuesday night fixture and an article on the excursion appeared in BMH30. Spotland had always been a popular destination for Gillingham fans. The away end had previously offered the combination of lovely meat and potato pies, warm mushy peas and home-made gravy and a blue, plastic fork to eat them with. However, those days had gone, the pies were standard fare and gravy now off the menu. Such was the lack of interest in the fixture from the Gills support that the two coaches that made the trip only had about thirty people each on board. It was good news for the four-strong BMH contingent, who had two seats each.

After leaving at 12.30pm, we were at Rochdale an hour and a half before kick-off, ‘This would have been ideal at Blackpool, Scarborough or even Halifax, but it is less so at Rochdale because, as anyone who has ever been there knows, Spotland is to Rochdale what Strood Sports Centre is to the Medway Towns, i.e. it is in the middle of nowhere.’

Inside the ground, with kick-off fast approaching, it became apparent that our support fell into two distinct categories, ‘It only gradually dawned on people, but the whole Travel Club, as opposed to the Away Travel coachload, seemed a little the worse for drink. Now, normally, they are rather staid, predictable and reserved, save for a couple of notable exceptions. In fact, some are terminally miserable but, at Spotland that night, they all seemed in unusually high spirits. Gradually it became known that they had left at 12 noon and had breezed into Rochdale at about 5pm.

With nothing to do in the vicinity except go in the Social Club or pub, this was exactly what they had done. Two and a half hours later and it was easy to spot who had been on their coach. They were all swaying gently, beaming happily, slurring their speech, glowing with life, making more noise than usual and embarking on regular trips to the ‘loos with a view’. The Gents in the away end at Spotland were situated in one corner at the top of the away terrace, with a fairly low wall and no roof, which meant that, unless you were very short, you could peer over the wall whilst taking a leak, thus missing none of the action on the pitch.

After Rochdale had been 1-0 up at half time, ‘The second half was altogether more promising as the Gills got their act together. Unfortunately, that un-coordinated bundle of youthful humanity that is Andy Arnott was playing, and not too well at that. As the Gills upped a gear, his brain dropped into neutral and he missed two easy chances. I then let go a verbal volley of rather uncomplimentary advice at the young lad, before being gently told by Si that l was standing three feet from Arnott’s Dad.’ Liburd Henry equalised for Gillingham and we held on for a 1-1 draw. The two coachloads of fans got back to the Medway Towns at 2am.

It seemed like Andy Arnott generally wasn’t very popular with our supporters. A feature on the away trip to Doncaster detailed how the striker had ended up in goal (with only two substitutes named in those days, clubs tended to select outfield players to be on the bench), following goalkeeper Scott Barrett’s sending off, late on in the game, for a professional foul, ‘Arnott played better in goal for six minutes than he had managed in the previous eighty-four, which explains why we didn’t score but managed not to concede any more goals after Barrett had disappeared to the dressing room.

The Gills were beaten 1-0 and, although bottom-side Northampton also lost, they leapfrogged us in the table, to dump Gillingham at the foot, courtesy of having scored twice that day. At the time, the league position of clubs equal on points was determined by the number of goals scored.

BMH had made regular requests for the perimeter fences at Priestfield to be taken down and they were finally removed at the Rainham End during the early part of 1992-3, with the visit of Torquay United at the end of October 1992 the first time that Gills fans in that part of the ground had had an unobstructed view of the action for twelve years. Although the Town End fences were also due to come down ‘in the not too distant future’, it wasn’t until the summer of 1995, following Paul Scally’s arrival at the club, that Priestfield finally became fence-free.