Brian Moore’s Head returned for its second season in August 1989, with a thirty-six page issue eight and new printers, Sheffield-based Juma taking over the role that it would retain for the remainder of the fanzine’s life.

Another change at BMH was that Rob, one of the founding editors, had escaped from Gillingham and was undertaking a year’s teacher training in the north east, leading to the fanzine’s base becoming fellow editor Simon Baker’s Rochester residence.

I had joined the editorial team in the summer and had turned out for the Head’s five-a-side outfit in the inaugural ‘Planetarium Trophy’ tournament, which was reported on in the first edition of the 1989-90 season. A three team extravaganza, it was evident that BMH’s strengths lay in writing about football, not actually playing it, as we lost both our games, including a 13-2 defeat in our opening fixture, against Dartford fanzine ‘Light At The End Of The Tunnel’, which damaged our chances of lifting the trophy beyond repair.

In our second match, the euphoria of building a 3-1 half-time lead against fellow Gills’ fanzine, ‘The Donkey’s Tale’, was soon dissipated as we contrived to lose by a 7-6 scoreline. The Dartford boys lifted the trophy and were no doubt singing all the way back to Watling Street.

The fanzine had actually made money from the seven issues produced during 1988-89 and the £90 profit made was donated to the Hillsborough Disaster Fund, which had been set up following the tragedy at the FA Cup Semi-Final in April 1989 that had claimed, at that stage, ninety-five lives.

As well as guaranteeing admission, traditionally the other main advantage of buying a season ticket is the saving on cost, when compared with paying on a match-by-match basis. However, back in 1989-90, financially-speaking, season tickets for Gillingham were not an attractive proposition. Terrace admission for the Rainham End for adults cost £3.70 per match, with the total for attending all twenty-three home league fixtures coming to £85.10. An adult season ticket for that area was priced at £85, giving season ticket holders a saving of 10p! To actually save the ten pence, season ticket holders would have to go to every game, as soon as they missed one, they would be worse off compared to paying on an individual match basis.

The club later admitted that due care and attention had not been taken with regard to setting the season ticket prices. BMH kindly provided readers with a few ideas as to how season ticket holders could spend the ten pence they’d saved by signing up for the whole campaign in advance. These included, ‘Put it on a large piece of paper and draw around it many times. Colour the circles in and you have created an attractive and cost-effective wallpaper’ and ‘Buy five season tickets and then buy issue 9 of BMH.’

The article ‘Reasons to be cheerful’ contained highlights of Gillingham’s 1988-9 season, ‘brought to you after hours of painstaking research (actually it involved a couple of minutes frantic scribbling on scraps of waste paper and used toilet roll tubes).’ These included, ‘Thinking up the “Never mind the relegation” cover months before we could use it and knowing we would be able to, later in the season’, ‘Watching a boy falling off his bike on the way back from Bristol (much better than the game)’ and ‘Walking through the turnstiles at Fulham with a “Brian Moore’s Head Says No To ID Cards” balloon attached to my shoulder.

It caught on the metal edging and burst, causing the turnstile operator to have a near heart attack and me to go temporarily deaf in one ear. I was also later informed that the policeman standing outside looked like he had been shot.’ One of the BMH team had been at Fulham’s home game with Reading earlier in the 88-9 campaign and the programme for the match had included a review of the Royals’ fanzine ‘Elm Park Disease’, so he sent a couple of copies of Brian Moore’s Head to the Craven Cottage club, several weeks before our visit. However, no review appeared in the matchday magazine for our match there, prompting BMH to ask why. The reply received from Fulham made for interesting reading, ’I received the copies of your fanzine and checked with Gillingham FC as to whether they would object to a reference in our programme. I was told that they would prefer to omit any reference to your magazine and, since we do not wish to cause offence to our visitors in an official Fulham publication, I therefore decided not to use the material you sent. I hope you can understand the reason for this and thank you again for sending copies of the magazine.’

Issue eight saw the first appearance of the fanzine’s fictitious columnist, ‘The Expert’, an old-school patriotic writer who condemned the modern game, harked back to the ‘golden era for the country and football’ and mentioned England’s World Cup Final win in every piece he wrote. His introductory offering included his view that the ‘Football Membership Scheme is the best thing to happen to the game since Sir Alf’s England team gloriously defeated the world in 1966.’

The expert wanted even more extreme measures, with all convicted thugs to have the word ‘hooligan’ permanently tattooed on their foreheads, to ‘make them think twice before indulging in their odious practices, dragging the Union Jack through the mud and bringing disgrace on the Empire.’ In the following edition, the expert bemoaned the fact that the season was too long, ‘Football was in a better state when the Cup Final provided a fitting finale to bring the curtain down in April. We could then rest, and enjoy a long break during the period more suited to the crack of leather on willow, and come back with our batteries recharged at the end of August, ready to start afresh.’

In issue nine, the expert was joined by his wife, who also penned an article, on the subject of football hooligans, ‘Put them in the Army, that’s what I say, my husband fought for this country and it never did him any harm, teach them some discipline, a good thrashing, that’s what they need. We never had soccer louts in my day, 70,000 every week and never a hint of trouble, football was football in those days, none of these namby-pambies with their flash cars and shin pads.’ Also under attack were the parents, who apparently weren’t interested in teaching their children discipline, ‘It’s all satellite recorders and compact gramophones, we never dreamed of such things when I was a girl, we had to make our own entertainment, we’d all sit in the corner wishing we could afford a piano, mind you we were poor but we were happy, and we had respect for law and order, not like all these soccer thugs with their long hair and ...’

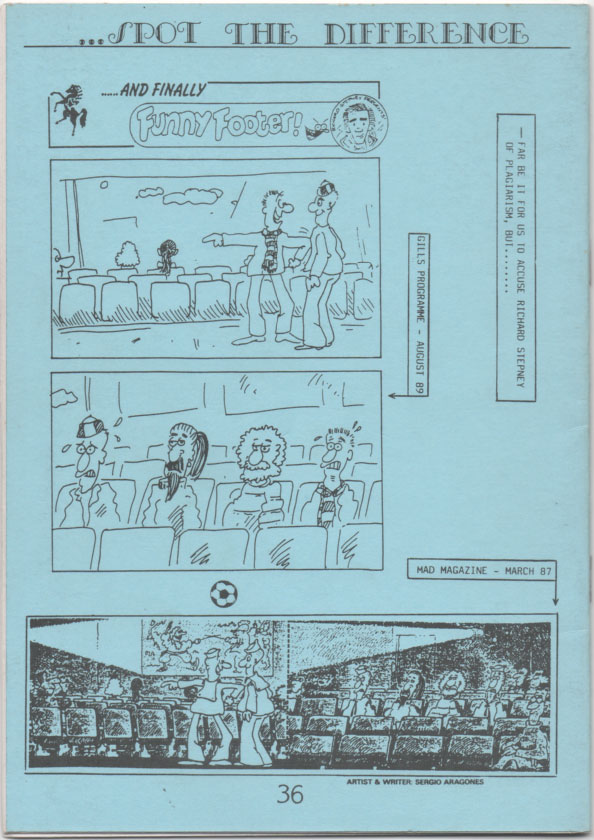

The Gills programme at the time included ‘Funny Footer’, a cartoon by Richard Stepney. Unfortunately, BMH caught him ripping off another artist’s work, with one of his efforts in August 1989 looking remarkably similar to a cartoon that had appeared in Mad magazine two and a half years earlier. After BMH had highlighted this in the back cover of issue nine, Stepney promptly disappeared from the matchday magazine!

What is probably best described as over-enthusiastic endeavours by the Metropolitan Police at an early 1988-9 League Cup tie at Leyton Orient was covered in both issues nine and ten by BMH. The Gills had lost the first leg 4-1 at Priestfield and it was only the die-hard followers who bothered with the game at Brisbane Road. Articles in the home club’s ‘Leyton Orientear’ fanzine and Exeter’s ‘The Exe Directory’ had told tales of away fans at Orient being thrown out of the ground for no apparent reason. The first half of our game in east London passed without incident, but a few fans noticed the Police sizing up the Gillingham contingent during the interval.

Early in the second period, the O’s missed a penalty, leading to the Met wading in to the away end and removing three lads who were doing no more than celebrating a rare piece of good fortune. The incident led to vehement protests, by other visiting fans, that continued after the final whistle. A senior Officer did appear after the game and, to his credit, spoke to the supporters, ‘He didn’t, however, manage to convince any of us (I don’t think he was convinced by the charge sheets his officers had provided him with – the charge had been changed to “running down the terrace”, an obvious hanging offence, especially as they were standing about five yards from the front)’.

Various letters of complaint were sent and some of the replies received were published in issue ten. One from the Metropolitan Police mentioned that the Police officers’ duty was to ensure good order in the stadium and that they needed to act on their own discretion to do so, ‘The difficulty facing them is to decide whether the behaviour has degenerated from over-enthusiasm to unruly or disorderly behaviour. On this occasion, the officers concerned obviously believed that it was necessary to remove the three persons concerned, with a view to “nipping in the bud” any “likelihood of general disorder”’.

Cover star of both the opening two issues of the season was forward Pat Gavin, who, having joined the club from non-league Hanwell Town during the previous campaign, had broken into the first team towards the end of 1988-9, and had shown potential. During the close-season, Gillingham failed to register the player’s contract. Leicester manager David Pleat found out about this and promptly signed Gavin. One writer’s opinion, printed in BMH, was that ‘The Pat Gavin affair was the low point of the summer.

From what I gather, Leicester and the player did nothing wrong and we were simply guilty of an administration error. The ethics of the move may be a bit dubious but football can be a cruel game. I do find it staggering that Leicester had apparently offered up to £250,000 before they got him for nothing – this for a player who had made just thirteen league appearances, admittedly scoring seven goals in a struggling side.’ Gavin was soon back at Priestfield, with Leicester, obviously feeling a tad guilty about the manner in which they had signed him, loaning him back to us for the season.

‘Typical Awayday’ in issue ten recalled an away match from early in the 1989-90 campaign that entailed a nightmare coach trip to Hartlepool. One coach didn’t arrive until the second half was underway, ‘Finally, at 4.10pm, we pulled up outside the ground and sixty people scrambled to get out the door all at once. The Police smiled sympathetically and let us through a side gate without paying. First things first – the latecomers split into two groups. Eight hours on a coach without stopping meant a toss-up between the loo and the food hut. Then we regrouped on the terrace, determined to make the most of the last half-hour. Inevitably, it started to rain.’ One of the other two coaches had only arrived two minutes late for the game, ‘mainly because their driver watches the football, so made sure they got there as quickly as possible.’ Coach three turned up fifteen minutes after kick-off.

Those who just saw the last half an hour only waited a little over ten minutes for a Gills goal, Lee Palmer equalising, the home side having taken a first half lead. Palmer then had another effort ruled out for offside before Peter Heritage put us 2-1 up with seven minutes remaining, ‘Ironically, having missed the first hour, we stood frantically whistling for time with five minutes remaining.’ In the final minute, Gillingham conceded their fourth penalty in three games. Only one of the previous three had been scored, ‘but none of us thought we could survive again.’ Ron Hillyard dived and saved his nineteenth penalty for the club and we held on for a 2-1 victory.

BMH10 had consisted of forty pages and was the biggest issue yet. Still priced at 50p, the fanzine was going from strength to strength, with the print run up to 1,000 copies, a phenomenal number, seeing as Gillingham’s average home gate at the time was less than 4,000.